Josef Jungmann. Unification of the Slavic languages

The year 2023 marks the 250th anniversary of the birth of Josef Jungmann, a brilliant Czech philologist, linguist, one of the founders of the modern Czech language and a figure of the Czech national revival.

Material prepared by: Boris Kogut.

To tell readers about this brilliant Czech scientist, I travelled to his hometown, to the places where he was born and grew up, talking to the guide and the locals. In the small Czech town of Hudlice, near the city of Beroun, it is impossible not to notice the signs "Josef Jungmann's Family House".

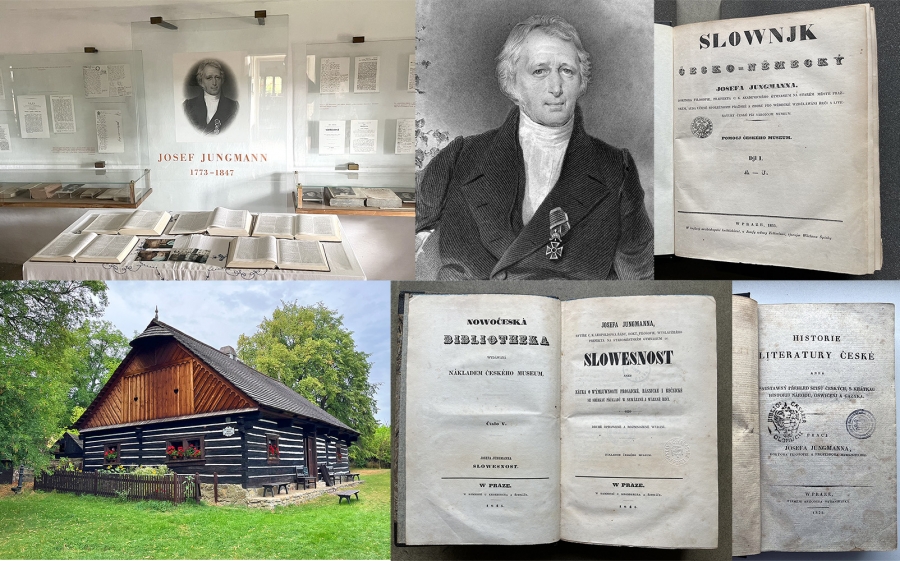

First, behind a wooden fence, I saw a monument to the brilliant philologist from 1873, then a beautiful log cabin from 1718. The furniture from this period has been arranged in the house as it was in Josef's lifetime. The family home of the famous philologist now houses an exhibition about him and his life's work. Josef, the son of a farmer, was educated at the Prague Gymnasium and the University of Prague at the Faculty of Philosophy and Law.

From 1800 Josef Jungmann taught at the Gymnasium in the Czech town of Litoměřice. In 1815 he moved to Prague, where he became a teacher of the humanities at the Old Town Gymnasium. In 1817 he obtained a doctorate in philosophy and law. While still at the Litoměřice Gymnasium, Jungmann gave private lessons in the Czech language, which at that time had to be done almost secretly, and he continued to do so in Prague. He was twice Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Prague, and in November 1939 he was elected Rector.

Jungmann devoted all his energy and knowledge to a single task: to free Czech society from the state of slavery into which it had fallen under the influence of historical events. The basis of Jungmann's programme was the linguistic unity of the nation, and he was deeply convinced that educated people, people of science, should bring knowledge to the masses, and therefore they were obliged to write and speak Czech. His translations of the great works of world literature, which were no longer just free retellings, were of great importance for the development of the Czech language.

Jungmann specifically chose difficult works of fiction for translation (e.g. Paradise Lost by John Milton, Bürger's ballad Lenora, Schiller's Ode to Joy, many works by Goethe, The Tale of Igor's Campaign, etc.).

For translations, he lacked the vocabulary of the Czech language at that time, and Jungmann experimented boldly. He revived old Czech words, borrowed words from other Slavic languages, especially Russian and Polish, and, when necessary, created entirely new words.

For example, he replaced the Russian word 'air' (vozduch) with the Czech word vzduch, or 'nature' (priroda) with the Czech word příroda. Jungmann explained and created new words unknown to the Czech public at the beginning of the 19th century, such as: záliv ("bay"), půvab ("charm"), okolnost ("circumstances") and many others. Jungmann spoke not only many foreign languages, but also all the Slavic languages. In his youth he was an advocate of the unification of the Slavic languages.

Based on his rich experience as a translator, Jungmann wrote the first Czech textbook of literary theory, Slovesnost. In 1825 he published the comprehensive History of Czech Literature, which is still the most valuable bibliographical survey of old Czech literature. The culmination of his work is the five-volume Czech-German Dictionary, one of the most outstanding works of the Czech national revival.

A square in Prague is named after Josef Jungmann, and a monument to the scientist was unveiled there in May 1878. Under the windows of the National Museum in Prague, Josef Jungmann's name is immortalised among seventy-two great personalities of Czech history. Josef Jungmann was undoubtedly the most outstanding personality of the Czech National Revival. His activities were always directed towards one goal: the renewal of the Czech language and thus the revival of the nation.